Edit : I just (re-)discovered ZenHub which is a highly advanced Google Chrome extension for Agile project management inside GitHub. Basically, ZenHub brings a lot of features inside the GitHub UI by connecting to your GitHub account (like the usual “Sign in with GitHub” button does), such as Scrum boards, burndown charts, as well as a lot of tiny yet handy extra features. We will try it seriously on an upcoming project at Edenspiekermann, but it definitely goes in the way of keeping things inside GitHub, including project management.

Pssst! I am currently looking for my next job opportunity for March 2026!

Read more on LinkedIn. ✨

This article is the result of a discussion about development workflow with one of our Scrum Masters at Edenspiekermann. Therefore, it assumes you have basic notions of Agile and Scrum. If you don’t, you still might benefit from reading the article but might be missing some keys to fully appreciate it. It also uses (although does not rely on) the Gitflow workflow.

In this short document, I try to describe what I feel would be a great workflow for me, using GitHub as a central point rather than having a collection of tools. Obviously, this standpoint is highly developer-centric and might not fit all teams / projects.

Given how long this article is, here is a table of contents so you can quickly jump to the section you want:

- Introduction

- What problem does it solve

- What problem does it introduce

- Creating the pull-request

- Naming the pull-request

- Filling the description

- Using comments

- Reviewing the pull-request

- Merging the pull-request

- Tip: using labels

- Tip: using assignees

- Tip: using milestones

- Tip: using issues

Introduction

Below is a short and informal methodology on how to use GitHub as a project workflow, heavily relying on pull-requests. While it might sound scary as first, this approach actually has a lot of benefits that we’ll investigate further in the next section.

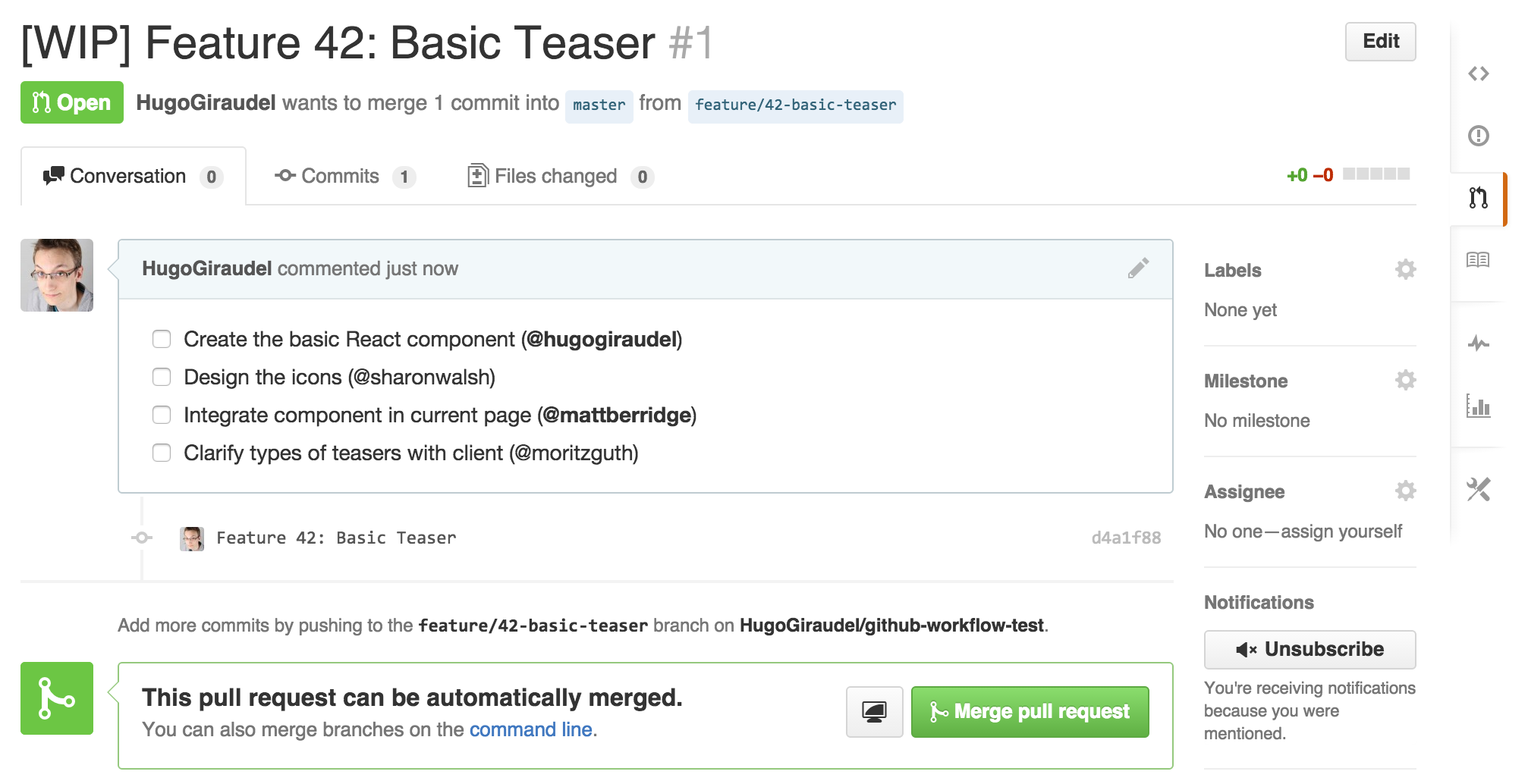

The rough idea is that at the beginning of a sprint, we create a(n empty) pull-request for all user stories. In the description of the pull-request, we write tasks in (GitHub Flavoured) Markdown using GitHub support for checkboxes. Then, affected developers commit their work to this branch, progressively checking out the tasks. Once all tasks from a pull-request have been treated, this one can be reviewed then merged.

What problem does it solve

- The code, code reviews, stories and tasks are all centralized in the same place, making it very easy for a developer to jump from one thing to the other.

- ScrumDo and other process tools are not always the best place for discussions and commenting, while GitHub is actually meant for this.

- GitHub has email notifications, which is helpful to know what’s going in the project and where a developer might need to get involved.

- GitHub has a lot of handy features, such as labels, Markdown, user pinging and code integration, which makes it a good tool for managing code projects.

- Bonus: Slack has GitHub integration, making the whole process seamless.

What problem does it introduce

Everybody, from the Scrum Master to the Product Owner, needs a GitHub account. It actually is only a matter of minutes, but it still needs to be done for this workflow to work correctly.

Creating the pull-request

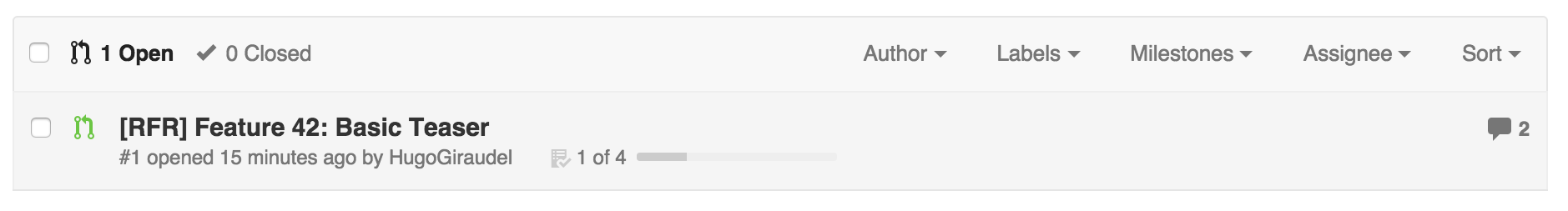

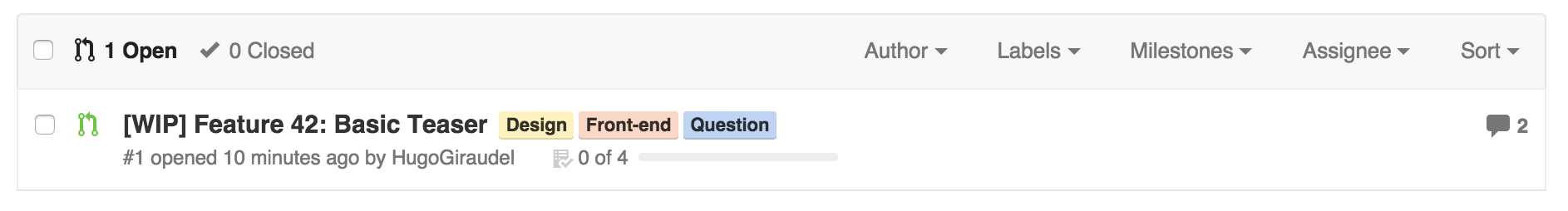

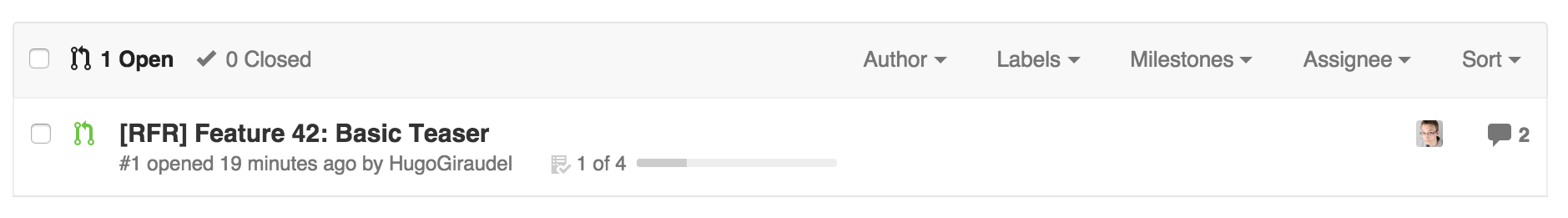

The idea is that every feature involving some development has its own pull-request opened at the beginning of the sprint. Tasks are handled as a checklist in the description of the pull-request. The good thing with this is that GitHub is clever and shows the progress of the pull-request in the list view directly.

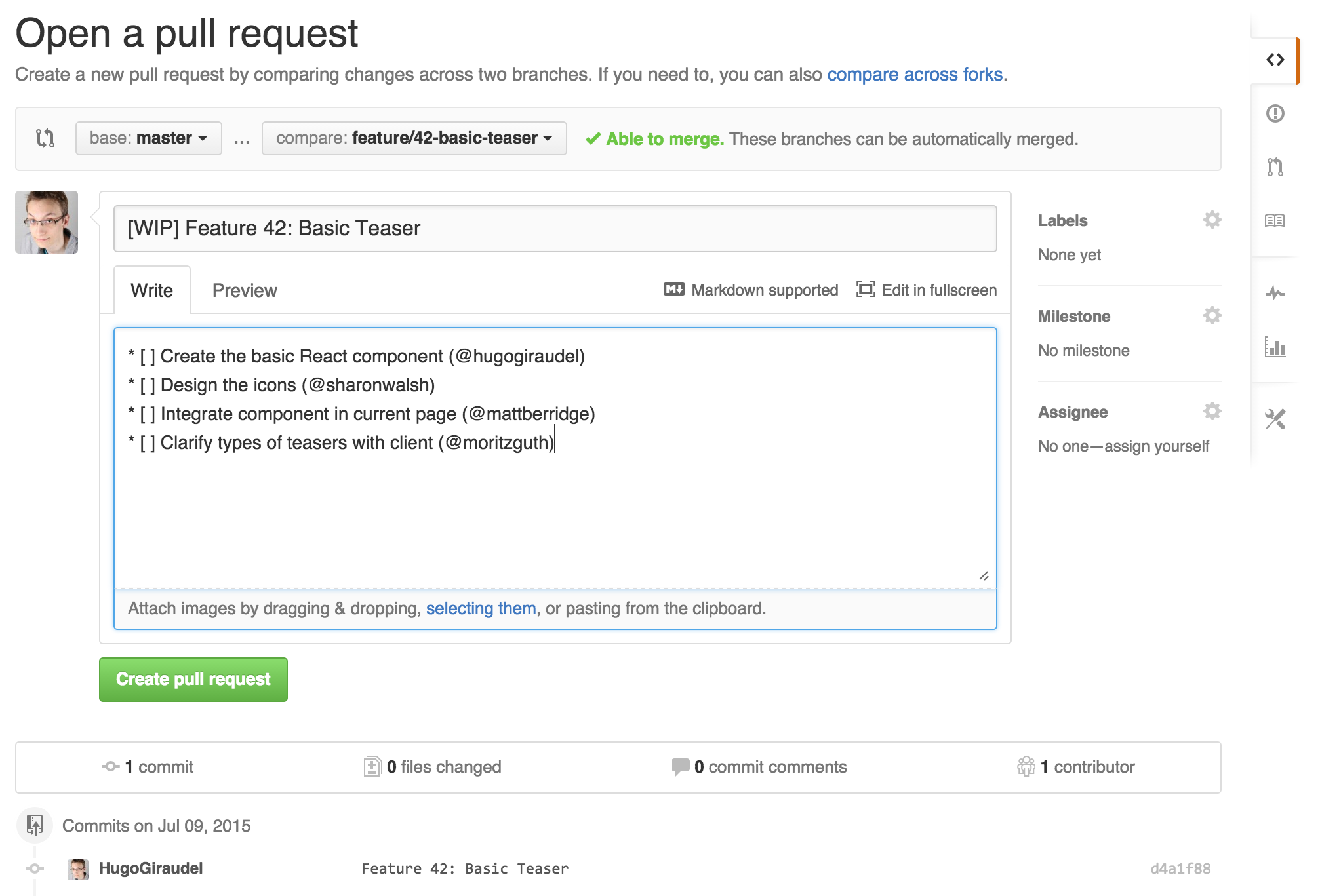

For all stories involving development, create a branch named after the story and open a pull-request from this branch to the main one. When sticking to Gitflow conventions, the main branch is develop, and story branches should start with feature/ (some might start with fix/ or refactor/). Then, we usually put the number of the story first, and a slug for the story goal (e.g. feature/42-basic-teaser).

Opening pull-requests can be done directly on GitHub, without having to clone the project locally or even having any Git knowledge whatsoever. But only when there is something to compare. It means that it is not possible to open a pull-request between two identical branches. Bummer.

To work around this issue, there are two options: either waiting for the story to be started by someone (with at least a commit) so there is actually something to compare between the feature branch and the main branch. Although that is not ideal as the idea would be to have it from the beginning of the sprint so that all stories have their own PR opened directly. A possible workaround to this issue would be to do an empty commit like so:

# Creating the branch

git checkout -b feature/42-basic-teaser

# Adding an empty commit (with a meaningful name) to make the pull-request possible

git commit --allow-empty -m "Feature 42: Basic teaser component"The point of this commit is to initialize the branch and the feature so that a pull-request can be created on GitHub.

At this point, head onto the home of the GitHub repository and click on the big ol' green button. Then, create a pull-request from the relevant branch to the main one (automatically selected). That’s it! For more details about how to name and fill the pull-request, refer to the next sections.

Naming the pull-request

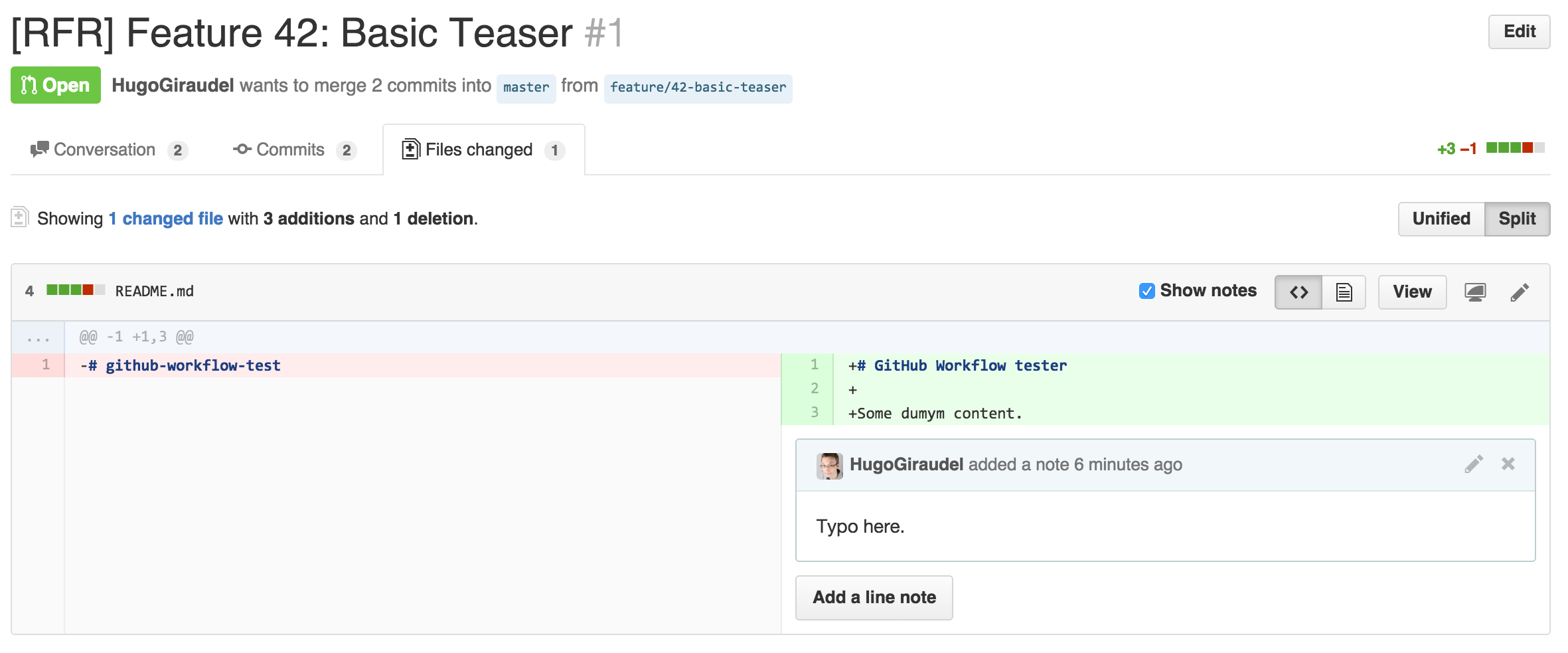

Name the pull-request after the feature name, and prefix it with [WIP] for Work In Progress. This will then be changed to [RFR] for Ready For Review once the story is done (see Reviewing the pull-request). If it is someone’s specific job to merge pull-requests and deploy, you can also change the name for [RFM] (for Ready For Merging) after the reviewing process so it’s clear that the feature can be safely merged.

Note: depending on your usage of GitHub labels, you can also ditch this part and use WIP, RFR and RFM labels instead. I prefer saving labels for other things and stick the status in the PR name but it’s really up to you.

Filling the description

In the description of the story, create a list of tasks where a task is a checkbox, a short description and importantly enough, one or several persons involved in the making. From the Markdown side, it might look like this:

* [ ] Create the basic React component (@KittyGiraudel)

* [ ] Design the icons (@sharonwalsh)

* [ ] Integrate component in current page (@mattberridge)

* [ ] Clarify types of teasers with client (@moritzguth)

As long as all actors from a project are part of the GitHub organisation behind the project, everybody can edit/delete any comment, so anyone is able to add new tasks to the description if deemed necessary.

Note: GitHub Flavoured Markdown will automatically convert [ ] into an unticked checkbox and [x] into a ticked one. It will also remember the state of the checkbox so you can actually rely on it.

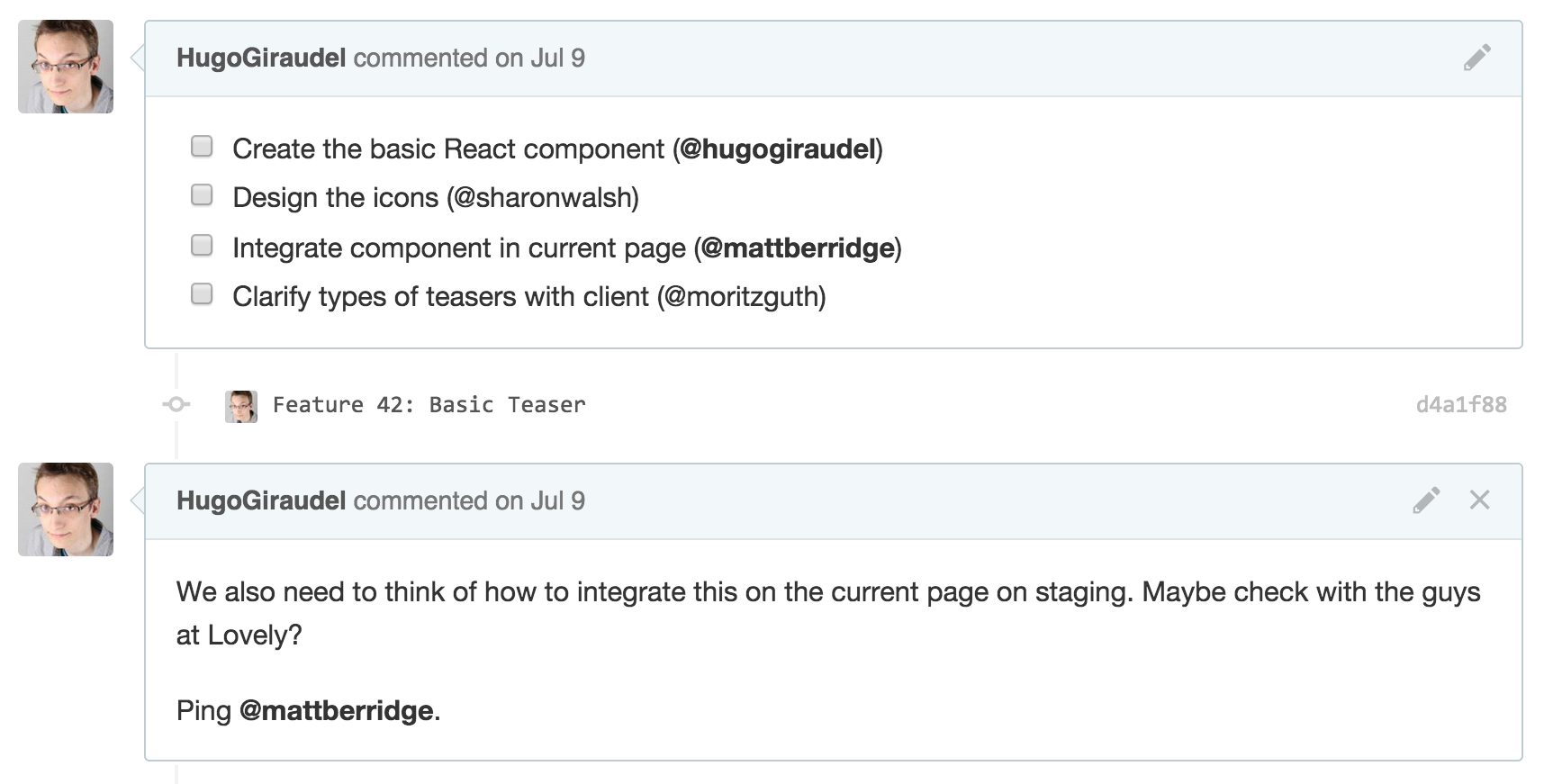

Using comments

The comments on the pull-request can be used to discuss the story or specific tasks. We can safely ask questions in there, tagging relevant contributors by prefixing their GitHub username with a @ sign, include code blocks, quotations, images and pretty much whatever else we want. Also, everything is in Markdown, making it super easy to use.

Reviewing the pull-request

Once all checkboxes from the description have been checked, the name of the pull-request can be updated to [RFR] for Ready For Review. Ideally, the person checking the last bullet might want to ping someone to get the reviewing process started. Doing so avoid having a pull-request done but unmerged because nobody has reviewed it.

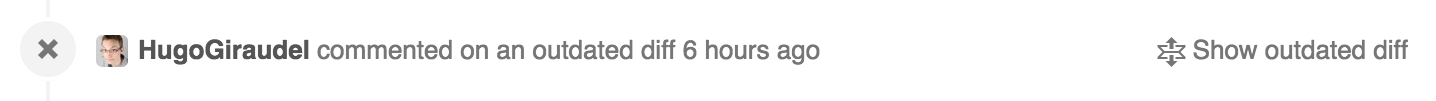

To review a pull-request, we use GitHub inline comments in the Files changed tab. In there, we can comment any line to ask for modification. Adding a line comment notifies the owner of the pull-request so that they know they have some re-working to do, and the comment shows up in the Conversation tab.

When updating a line that is the object of an inline comment, the latter disappears because it is not relevant anymore. Then, as comments get fixed, they disappear so the pull-request remains clean.

Merging the pull-request

Once the review has been done, the pull-request can be merged into the main branch. If everything is fine, it should be mergeable from GitHub directly but sometimes there are potential conflicts so we need to either rebase the branch to synchronize it with the main branch or merge it manually. Anybody can do it, but the pull-request owner is probably the best person to do it.

Note: in order to keep a relevant and clean commit history, it would be wise to keep commit messages clear and meaningful. While this is not specific to this methodology, I think it is important enough to stress it.

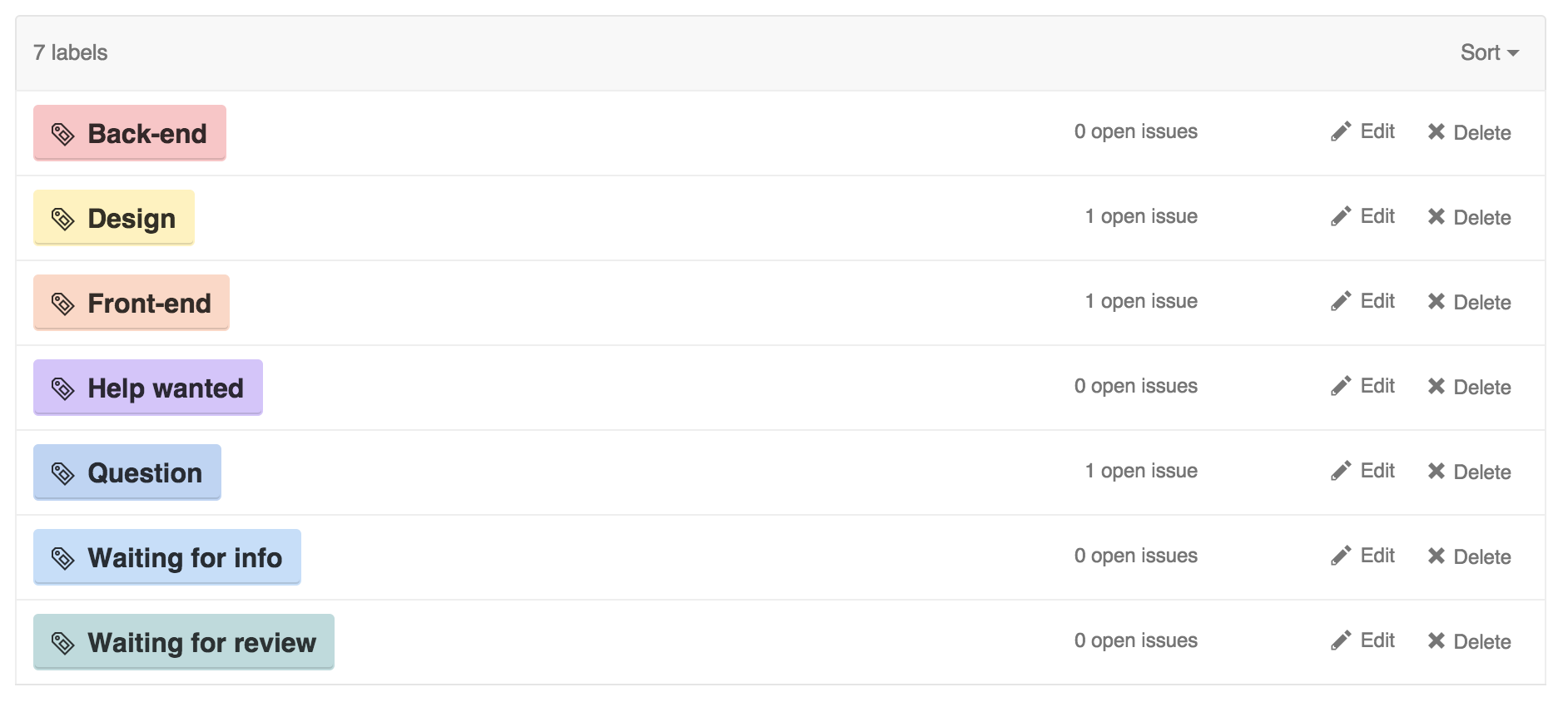

Tip: using labels

Labels can be very helpful to add extra pieces of information to a pull-request on GitHub. They come in particularly handy as they show up in the list view, making it visible and obvious for everybody scanning through the open pull-requests.

There is no limit regarding the amount of labels a project can have. They also are associated with colors, building a little yet powerful nomenclaturing system. Labels can be something such as Design, Frontend, Backend, or even Waiting for info, Waiting for review or To be started. You name it.

On a project involving design, frontend, backend and devops teams, I would recommend having these team names as labels so each team is aware of the stories they have to be working on.

Tip: using assignees

More often than not, a story is mostly for one person. Or when several actors have to get involved in a story, it usually happens one after the other (the designer does the mockup, then the frontend developer does the component, then the backend developer integrates it in the process, etc.). Because of this, it might be interesting to assign the pull-request to the relevant actor on GitHub, and change this assignment when needed.

Tip: using milestones

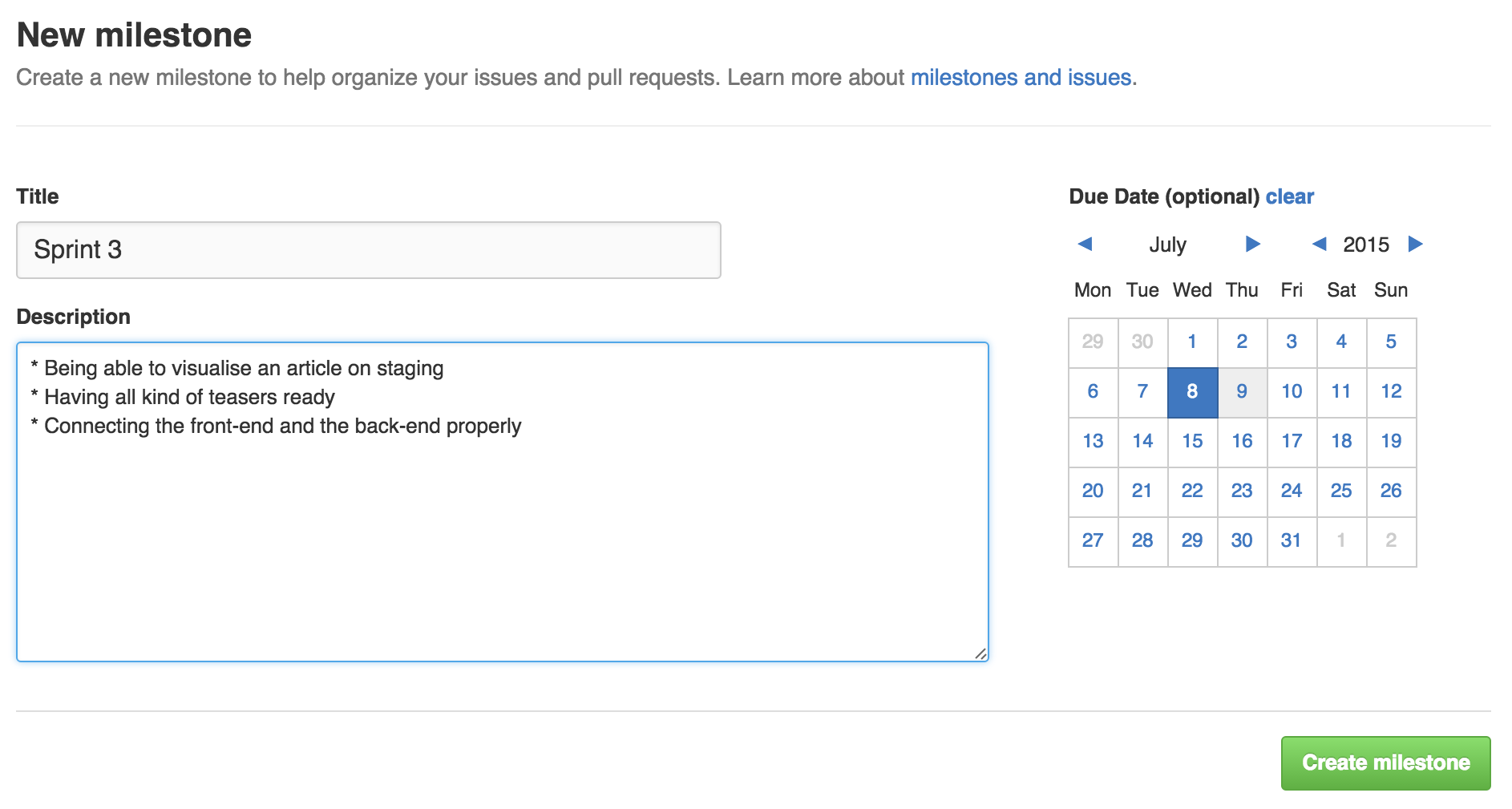

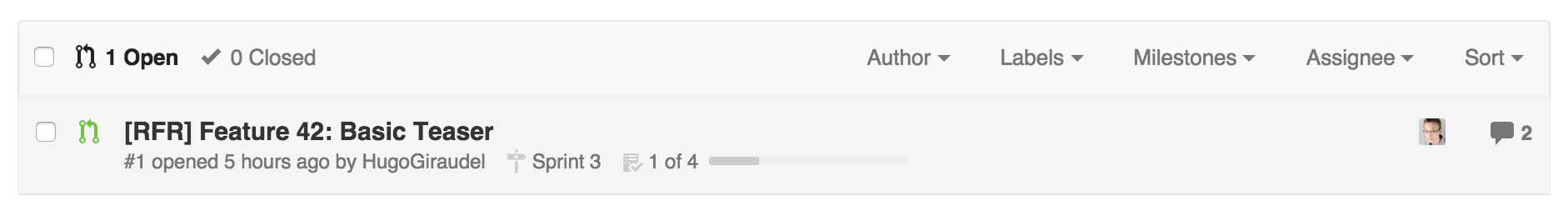

Because GitHub is a platform for Git, it is a great tool to conserve a clean history of a project. One way to achieve this goal (if desired), would be to use milestones. To put it simply, on GitHub a milestone is a named bucket of issues/pull-requests, that can optionally have a description and a date.

Applying this to a Scrum project could mean having a milestone per sprint (named after the number of the sprint), with a due date matching the one from the end of the sprint and the goals of the sprint in the description. All pull-requests (stories) would be tagged as part of the milestone.

While not very helpful for the develop because all open pull-requests are part of the current sprint anyway, it might be interesting to have this as an history, where all pull-requests are gathered in milestones corresponding to sprints.

Tip: using issues

The fact that this workflow is heavily focused on pull-requests does not mean that GitHub issues are irrelevant. Au contraire! Issues can still be used for additional conversations, bug reports, and basically any non-feature-specific discussion.

Also depending on the relationship with the client (internal or external), issues might be the good place for them to report problems, bugs and suggestions. Again, everything is centralized on GitHub: the pull-requests remain clean and focused on features; issues are kept for all side-discussions.

That is all I have written about it so far. I would love to collect opinions and have feedback about this way of doing. Has anyone ever tried it? How does it perform? How does it scale? What are the flaws? What are the positive effects? Cheers!