Pssst! I am currently looking for my next job opportunity for March 2026!

Read more on LinkedIn. ✨

One of the most frustrating kinds of outages is when everything seems fine on paper, except things are very much not fine and your users are yelling at you. The process is up. The logs are still flowing. The status page is all green. The usual metrics keep saying “all good”. Yet the reality is: no one is online, and nothing is moving.

This is the story of the watchdog service I built for our RPG game server: a small, external process that doesn’t care whether the server is technically alive, only whether the game is actually working. It’s designed to recover from deadlocks, runaway timeouts, population loss, and all those “it’s technically running” incidents that typically page you at 3am.

It’s relatively long, so here is a table of contents:

- Ensuring the server always runs

- Incident #1: running doesn't mean healthy

- Incident #2: healthy is all relative

- Incident #3: health checks are not live traffic

- Incident #4: when minutes last forever

- Why so many incidents?

- Bonus: meaningful status page

- Bonus: operational ergonomics

- Lessons learned

Ensuring the server always runs

For the most part, our server is very stable. Metrics are healthy: CPU is hovering around 20–40%, memory is stable around 55% with plenty room for activity bursts and latency is very low. So it never really goes down per se.

Still, I wanted to make sure the game server process always runs. And in the off-chance it doesn’t, I wanted to make sure it starts up on its own.

Because this cannot be managed by the server itself (since it would need to be running to guarantee it’s running), I went with a small external service: a watchdog. The setup is pretty straightforward: we register a new systemd service which executes a bash script as long-lived process.

Read the full service definition (with explanation comments).

# The [Unit] section describes when this service should start and how it relates to others.

# - After: ensures watchdog starts only after basic networking is configured.

# - Wants: additionally requests the network-online target so DNS/HTTP calls work.

# - StartLimitBurst: allows up to 5 rapid failures before systemd pauses restart attempts.

# - StartLimitIntervalSec: counts those failures within this 60 second window.

[Unit]

Description=Game Server Watchdog

After=network.target

Wants=network-online.target

StartLimitBurst=5

StartLimitIntervalSec=60

# The [Service] section defines how the watchdog process itself runs.

# - Type: runs the watchdog as a simple long-lived process (no forking).

# - User: drops privileges to the nameofuser user.

# - WorkingDirectory: runs the script from the repository directory so relative paths work.

# - ExecStart: executes the watchdog shell script that performs health checks and restarts.

# - Restart: relaunches the watchdog if it exits with a failure status.

# - RestartSec: waits 10 seconds between restart attempts to avoid thrashing.

# - KillMode: only stops the watchdog process on restart, not child processes such as the

# Rust server started by run.sh. This avoids killing a healthy server when manually

# restarting the watchdog service.

# - LimitNOFILE: raises the open‑file limit for the watchdog and Rust server.

# - StandardOutput: sends stdout to the journal so logs appear in journalctl.

# - StandardError: sends stderr to the journal as well for errors.

[Service]

Type=simple

User=nameofuser

WorkingDirectory=/path/to/game/server

ExecStart=/path/to/game/server/watchdog.sh

Restart=on-failure

RestartSec=10

KillMode=process

LimitNOFILE=16384

StandardOutput=journal

StandardError=journal

# Environment variables

# - Default to the production environment unless overridden.

# - Ensure HOME points to the nameofuser home directory.

# - Provide PATH so cargo/rust binaries are found even in non-interactive shells.

Environment="ENVIRONMENT=prod"

Environment="HOME=/path/to/game/server"

Environment="PATH=/path/to/game/server/.cargo/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin"

# The [Install] section controls how the service is hooked into boot targets.

# - WantedBy: starts the watchdog automatically in multi-user (normal) boot mode.

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.targetEvery 10 seconds, that bash script ensures there is a running game process. If it finds a problem 3 times in a row, it (re)starts the process. This is how a simplified version looks:

failure_count=0

max_failures=3

interval=10

is_server_running() {

pgrep -af game_server || true

}

start_server() {

./start_server.sh

return $?

}

while true; do

sleep "$interval";

if ! is_server_running; then

failure_count=$((failure_count + 1))

if [ $failure_count -ge $max_failures ]; then

if start_server; then

failure_count=0

fi

fi

else

if [ $failure_count -gt 0 ]; then

failure_count=0

fi

fi

doneAvoiding thrashing

During my tests, I faced some issue with thrashing, which is when the watchdog runs the bash script to start the server, and while this happens, detects again that the server is not running so executes the bash script again, and so on.

It normally doesn’t happen because the start script is very fast, but it can happen if cargo run ends up performing a build. In such a case, the script can take 1 or 2 minutes, which would be long enough for the health check to fail 3 times in a row again, and trigger yet another restart, effectively putting the watchdog in an infinite loop.

To avoid this situation, we can have a restart_server function that performs some automatic backoff.

start_server() {

./start_server.sh

return $?

}

restart_server() {

local now

now=$(date +%s)

local window=300 # 5 minutes

local max_restarts=3 # Max restarts in the window

RESTART_HISTORY=("${RESTART_HISTORY[@]:-}")

local recent=()

for ts in "${RESTART_HISTORY[@]:-}"; do

if [ $((now - ts)) -lt $window ]; then

recent+=("$ts")

fi

done

RESTART_HISTORY=("${recent[@]}")

if [ "${#RESTART_HISTORY[@]}" -ge "$max_restarts" ]; then

return 1

fi

if start_server; then

RESTART_HISTORY+=("$now")

return 0

else

return 1

fi

}It’s a lot of bash, but basically all it does is ensure no more than N restarts (max_restarts) within a X seconds window (300). A potential improvement would be to implement some exponential backoff instead.

Fixing a curious edge case

At some point, I noticed something curious: when restarting the systemd service (to update its configuration or whatnot), the game server would die (fortunately, I noticed that in our test environment). It took me a long time and some heated conversations with Cursor to figure out why.

It turns out that restarting a systemd service nukes all its subprocesses. So any process that was started by that service also gets killed.

The solution is to specify KillMode=process in the service definition so that it only restarts the service process itself, and none of its sub-processes.

# - KillMode: only stops the watchdog process on restart, not child processes

# which would include the Rust server started by the script. This avoids

# killing a healthy server when manually restarting the watchdog service.

[Service]

KillMode=processIncident #1: running doesn’t mean healthy

We had a situation where the server was technically running — in the sense that there was a process, but the game server loop was actually kind of broken (more on that later), and no player could play or sign in. This showed that just checking for the process existing was not enough.

Our Rust process exposes a tiny HTTP server for some webhooks. I thought I would add a health endpoint which simply returns 200 OK. From there, all we have to do is change our is_server_running implementation to ping that endpoint:

is_server_running() {

curl -fsS "http://127.0.0.1:1234/health"

}This is a clear improvement: it verifies not just that the server is running, but that it can respond.

Incident #2: healthy is all relative

Picture this: the health check consistently responds with 200 OK, the status page is green, our observability platform is happy… but no one else is. Players cannot log into the game, and online players are faced with a reconnection screen.

What happened was that our tiny exposed web server was alive and well, meanwhile the main accept loop was wrecked. So the watchdog kept getting successful pings, but that didn’t translate into the actual game server being healthy. So I ditched the HTTP health endpoint because it didn’t reflect the game’s actual state — players connect over websockets, so the watchdog should too. If the websocket loop is dead, the game is dead, even if HTTP says “200 OK”.

Instead, I thought the watchdog could open a short-lived websocket connection, send a health check packet, and expect a response back.

I didn’t really want to deal with all this in Bash though, so I introduced a thin Rust script in between to deal with the whole websocket layer (trimmed down and simplified below).

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error + Send + Sync>> {

let health_check_packet = create_packet(PacketType::HealthCheck)?;

let timeout_duration = Duration::from_secs(5);

let connect_result = timeout(timeout_duration, connect_async(websocket_url)).await;

let (ws_stream, _) = match connect_result {

Ok(Ok(stream)) => {

stream

}

Ok(Err(e)) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

Err(_) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

};

let (mut sender, mut receiver) = ws_stream.split();

let send_result = timeout(

timeout_duration,

sender.send(Message::Text(health_check_packet.into())),

)

.await;

match send_result {

Ok(Ok(_)) => {}

Ok(Err(_)) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

Err(_) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

}

let received_result = timeout(timeout_duration, receiver.next()).await;

match received_result {

Ok(Some(Ok(Message::Text(response)))) => {

match handle_packet(&response) {

Ok(packet) => {

match serde_json::from_str::<Packet>(&packet) {

Ok(PacketType::HealthCheckResponse) => {

let _ = sender.send(Message::Close(None)).await;

std::process::exit(0);

}

Ok(_) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

Err(_) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

}

}

Err(_) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

}

}

Ok(Some(Ok(_))) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

Ok(Some(Err(_))) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

Ok(None) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

Err(_) => {

std::process::exit(1);

}

}

}Then I modified the is_server_running function to execute that Rust script binary:

is_server_running() {

./target/release/health_check

}I felt way more confident with this change, because the health check actually communicated with the web server via a websocket, just like a player device would. With that, surely if the server was unhealthy, I’d be the first one to know.

Incident #3: health checks are not live traffic

The thing with a health check packet is that it’s not exactly like a real device sending packets. For a start, It’s not authenticated, and it’s kept very lightweight on purpose — it doesn’t actually ping all moving parts of the system.

To this day, I still do not fully understand why, but we had an incident where the watchdog was happy, but the server wasn’t. The latter kept sending healthy responses back, meanwhile all other packets were timing out. My assumption is that there was something else in the main packet handler that was broken, something the health check resolution didn’t hit.

Unfortunately, this happened at 3am when I was busy, you know, being fast asleep. I woke up around 7am to an absolute shitstorm, immediately restarted the server, and started looking into what happened and how we could make things more resilient.

We get hourly notifications about the server activity, and sure enough, there was an alarmingly low activity during the incident. So I thought maybe I could hook this up to the watchdog. If there are not enough players online, surely it means the server is whacked and should be restarted.

So when handling the health check packet on the server, we look at how many players are connected, and we compare it with our configured threshold (e.g. 100 or whatever we defined). If it’s lower than the threshold, we return a failed response.

if let Some(min_online_threshold) = config.min_online_threshold {

if metrics.online_players < min_online {

return HealthStatus::NotEnoughPlayers;

}

}Note: I’ve made it so that we can configure the threshold remotely. Not only does this enable us to have different thresholds for different environments, but it also makes it possible to disable this population check entirely by simply making it None.

This actually works quite nicely. During the next incident, players started getting disconnected. Since they couldn’t reconnectn, the server slowly drained out of online players. Eventually, the threshold was hit, the health check failed 3 times in a row, and the server was restarted. Yay!

Accounting for expected low traffic

One concern I had was how to handle times where we’d expect low or no traffic. There are 2 main cases for this:

- Infrequent planned maintenances. I was not overly concerned with this, because I knew I could still manually turn off the systemd service, which in turn would stop the watchdog. Not perfect, but still acceptable especially if documented.

- Post-deployment windows. We do not have blue/green deployments: our bootstrapping script runs

cargo build, then kill the existing server and immediately runscargo run. There is a brief 1–2 seconds window where players see a connection screen. My main worry was that the health check would see too few players shortly after a deployment, 3 times in a row, and restart the server again, effectively triggering a restart loop.

To work around the latter problem, I decided to define a “grace period”, during which the health check would not look at the population. For X minutes after the server starts, the population check would essentially be ignored, even if there are less players than the threshold. This allows for a slow refill of the player count.

// Keep track of the start time

start_time: RwLock::new(Instant::now())// In the health check, check if in grace period before the population check

let start_time = { *self.start_time.read().await };

let seconds_since_start = start_time.elapsed().as_secs();

let in_grace_period = seconds_since_start < GRACE_PERIOD_SECS;

if in_grace_period {

return HealthStatus::Healthy;

}Incident #4: when minutes last forever

It can take several minutes between the server reaching a deadlock state and enough players being offline for the health check to start failing. It may not seem much, but 5 minutes is a long time.

Gamers are notoriously vocal, and often dismissive of the complexity of running a high traffic performant system. Additionally, every minute the server is unavailable is a minute where there are no transactions, and a minute where people may think twice before spending money in the future. It’s a big deal.

I was curious to see how I could speed up the recovery.

One way would be to make the population threshold much much higher, but then you risk hitting false positives. Say you have an average of 1,000 players online at all times.

- You can say that anything below 200 players online is not normal. That means you need 800 players to time out and log out before your health check starts failing.

- Now you can bump that threshold to 500 or even 800 players, which means the health check will start failing way faster! But then, what if you have just a traffic dip for any reason. Maybe it’s New Year’s Eve, or there is a massive internet outage in the biggest market. It’s risky.

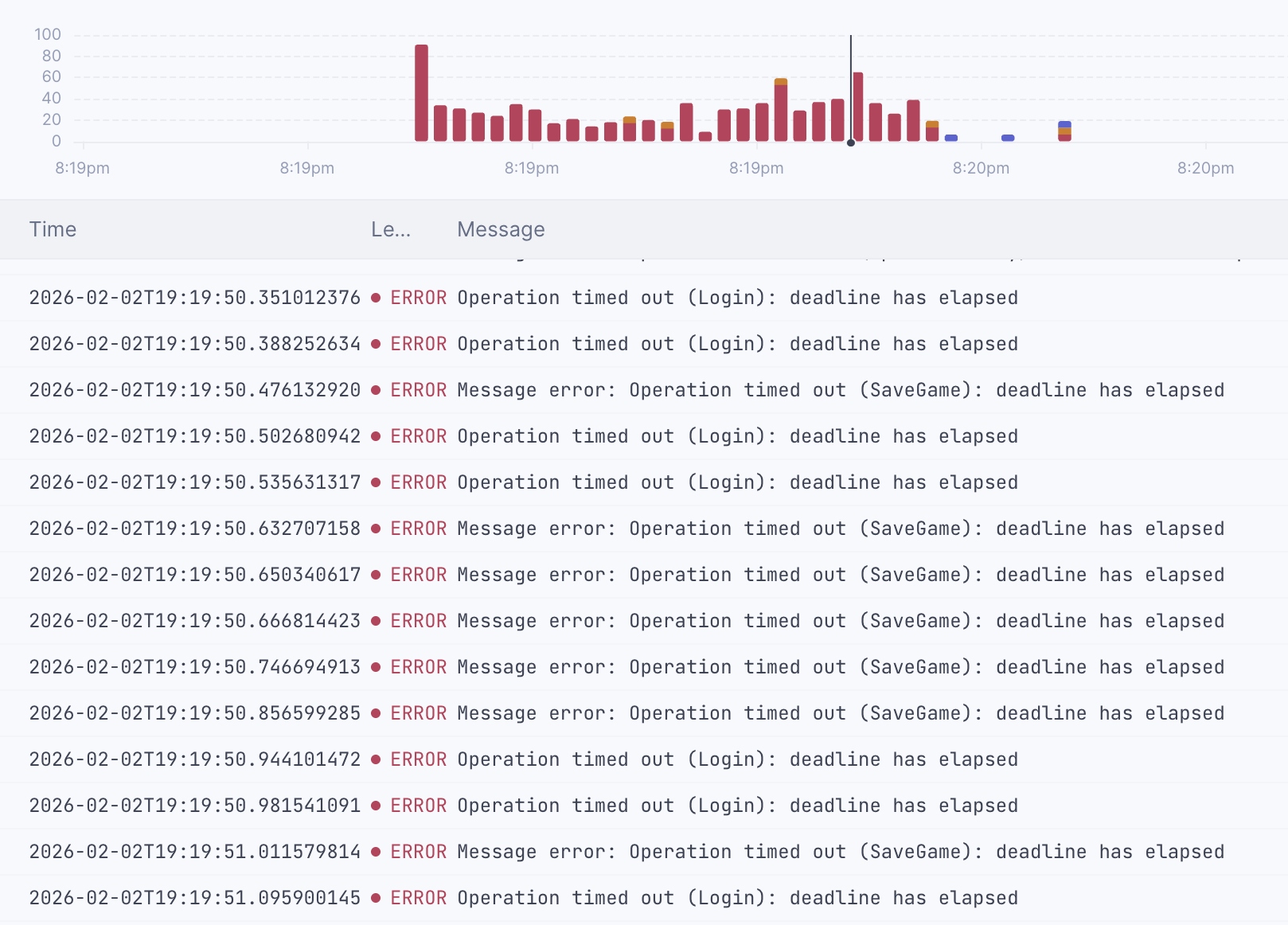

Instead, I decided to look into the main symptom for any major incident we had: timeouts. It always manifests the same way: all of the sudden, all client-side packets start timing out. The logs are all red and angry, everything just shows “deadline has elapsed”. There is no self-recovery either: it’s not a burst problem — it’s the runtime in a deadlock.

What if I could notice when this happens? To do so, I’ve started keeping track of when the server times a packet out. I’ve decided to use a SegQueue from the crossbeam_queue crate.

pub struct HealthCheckConfig {

pub(crate) min_online_players: Option<i32>,

pub(crate) max_timeouts_per_window: Option<u64>, // Assumed 30s

pub(crate) timeout_timestamps: Arc<SegQueue<Instant>>,

}fn record_timeout(&self) {

self.timeout_timestamps.push(Instant::now());

}This enabled me to implement a rolling window. The health check looks how many timeouts happened in the last 30 seconds.

fn count_timeouts_in_window(&self) -> Option<u64> {

self.max_timeouts_per_window.map(|_| {

let window = Duration::from_secs(30);

let now = Instant::now();

let cutoff = now.checked_sub(window).unwrap_or(Instant::now());

let mut count = 0u64;

let mut recent_timestamps = Vec::new();

while let Some(ts) = self.timeout_timestamps.pop() {

if ts >= cutoff {

count += 1;

recent_timestamps.push(ts);

}

}

for ts in recent_timestamps {

self.timeout_timestamps.push(ts);

}

count

})

}If it’s higher than a threshold, it fails.

if let Some(max_timeouts_threshold) = config.max_timeouts_per_window {

if metrics.timeouts >= max_timeouts_threshold {

return HealthStatus::TooManyTimeouts;

}

}It worked amazingly well. The next time we had an unfortunate deadlock, it spotted it immediately and restarted within 30 seconds — the time it took to perform 3 consecutive failed health checks. It could be made even faster by reducing the interval between health checks.

Why so many incidents?

That is a good question. They were not all caused by the same thing, but they ultimately all boiled down to the tokio runtime being stuck or starved.

- One incident was caused by an inappropriate usage of

futures::future::join_allin a high frequency loop. Any hung client would cause all other futures to wait, slowly queueing more and more futures that never resolve until tokio is starved. - One incident was caused by an occasional and hard-to-track multi-thread race condition causing 3 threads to wait on one another, effectively putting the tokio runtime in a deadlock.

- One incident was caused by another deadlock due to different locks being acquired in different orders across multiple threads, causing two threads waiting on one another indefinitely.

I’m still learning Rust and its intricacies. I’ve gotten better at diagnosing deadlocks, but they can be surprisingly difficult to pinpoint. Even professional teams occasionally struggle with this.

Bonus: meaningful status page

One unfortunate side-effect of all of these incidents is that a lot of them were not reflected on our status page. This is a problem because a) that’s kind of the only purpose of the status page and b) it erodes players’ trust in said status page.

Since its first version, the watchdog forwarded the health check status to BetterStack. On a successful health check, the watchdog sends a normal heartbeat. On a failed one, it sends a special “something is wrong” signal instead.

send_heartbeat() {

local is_healthy=$1

local heartbeat_url="$BS_HEARTBEAT_URL"

if [ "$is_healthy" != "true" ]; then

heartbeat_url="${BS_HEARTBEAT_URL}/fail"

fi

curl -sSf --max-time 5 --head "$heartbeat_url"

}Now that the watchdog detects rapidly if the game server is unhealthy, the status page actually reflects our notion of “the game is playable”, not just “some process is running”.

Bonus: operational ergonomics

From an operations perspective, I tried to make the watchdog as boring as possible. Still, there are a few cool things about it:

- It logs everything it’s doing (although not shown in this article for conciseness), and these logs go to BetterStack just like any other log from our system.

- It is configurable with environment variables that can be defined in the service configuration. So we can speed up the health check or modify the thresholds, just by updating the service config and restarting it — no downtime.

- The service definition is stored in the repository, versioned and documented. Modifying it is done like any other code, and redeploying it is done with a GitHub Actions that takes care or restarting the service.

Day‑to‑day, the team doesn’t think about the watchdog much; it just quietly does its job in the background. Speaking of which, this is a flowchart of the watchdog architecture:

Lessons learned

It’s been a journey, and a very stressful one at that. But also there were a lot of learnings and a fair deal of satisfaction from knowing the system comes more resilient with each improvement. Here are a few learnings:

- Rust makes it very hard to write broken code, but because everything is multi-threaded, race conditions and deadlocks are a real risk, and they can be very difficult to spot.

- System services are surprisingly simple, light and useful. First time writing one for me, but I’d definitely consider doing it again.

- “Up” is not the same as “OK”. Health checks that only look at process liveness or HTTP 200s are not bullet-proof.

- Home-made population and timeout checks are janky workarounds in a way, but they work great for us.

Is this perfect? Of course not. But in practice, this watchdog has been a huge quality‑of‑life improvement. It quietly restarts the game when things get weird, surfaces problems clearly in monitoring, and lets us sleep through incidents that used to require manual intervention.